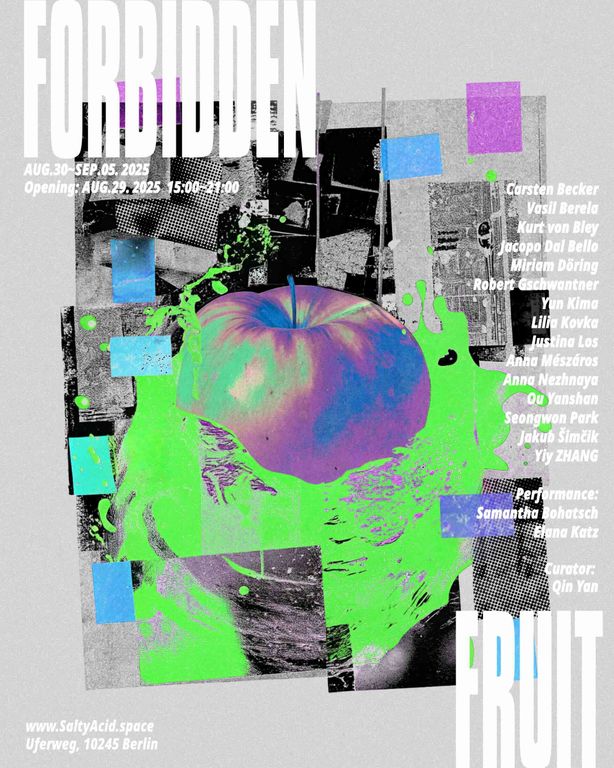

Forbidden Fruit

Exhibited Works

About the Exhibition

And the LORD God commanded the man, saying,

Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat:

But of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil,

thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die.

(Genesis 2:16–17, King James Version)

And the serpent said unto the woman, Ye shall not surely die:

For God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof,

then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.

(Genesis 3:4–5, King James Version)

The forbidden fruit, from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, symbolizes humanity’s fateful choice 1: to eat is to gain the the capacity for moral discernment, independent judgment, and free will – a turning point that marked the beginning of humanity's moral dilemmas and the unfolding of civilization. Why, then, would God forbid humanity from attaining such knowledge? If it encompasses both good and evil, why is it deemed taboo? One interpretation suggests that the prohibition is not a denial of knowledge itself, but a caution against the hubris of assuming divine authority—the illusion of being able to judge, define, and control the world, which becomes an invisible mechanism, subtly reshaping desire, value systems, and modes of action. When we learn to ‘know’, do we also begin to fall?

Staged on a houseboat drifting along Berlin’s Spree, the exhibition unfolds in a lived-in space shaped by everyday gestures, where metaphor ceases to be distant and instead comes intimately close. The boat itself emerges as a vessel of movement and transmission—not only across water, but across ideas, ideologies, and cultural systems. Through the distinct perspectives of 17 Berlin based artists, including two who engage the space through live performance, the exhibition charts these crossings in multiple, layered forms.

Several artists in the exhibition interrogate systems of standardization, consumerism, and power, exposing how seemingly neutral structures quietly shape, manipulate, and exhaust everyday life. By tracing the standardization of objects and colors within 20th-century German industrial and military systems, Carsten Becker reveals how rationalization — once celebrated as modern progress — hides violence in everyday life and becomes a tool of destruction in war. In Justina Los’s work, she shows how consumerism shapes contemporary life, exploiting psychology to erode ideals and aspirations, replacing them with a culture of consumption, habit, and fatigue. Reflecting on the futility of navigating the funding system, Anna Mészáros highlights how promised opportunities often reduce artistic efforts to a mere gamble under the control of power. Seongwon Park reconstructs urban structures through installations, highlighting overlooked details and showing how our attempts to interpret our surroundings are shaped by social norms, cultural contexts, and personal biases.

Others turn toward the entanglement of technology, virtuality, and the natural world, addressing both the promise and peril of progress. Vasil Berela’s sculptures straddle the boundary between the natural and the artificial, freedom and control, conveying a contemporary sci-fi sensibility while revealing that neither freedom nor technology offers absolute liberation, but carries risks of isolation, alienation, and corruption. In Miriam Dörring’s work, the body serves as a testing ground for power and environmental pressures, revealing how science, medicine, mythology, and politics exploit vulnerability to exert control, while exposing risks of manipulation and corruption. Robert Gschwantner creates works from PVC tubes filled with oil, polluted water, or mud drawn from human-altered European landscapes, exposing humanity’s desire to control nature through technology while leaving traces of pollution and destruction. Yun Kima’s installation merges digital fabrication and physical construction to explore how late-capitalist technologies reshape the subjectivity between the natural and the artificial, creating new lifeforms and altered realities that raise questions of agency, control, and ethical responsibility. Through neon installations, Anna Nezhnaya explores the interplay of reality and virtuality and the recontextualization of iconic imagery, revealing the environmental, cultural, and technological risks that emerge alongside shifting identities and value systems.

A different set of works engages with symbols of belief and identity, uncovering the fragility of human attempts at meaning. In Kurt von Bley’s work, analogue television meets the cross, symbols once promising salvation, now silent and broken, creating a “double interference” of technology and faith, revealing parallel suffering. Lilia Kovka transforms discarded beauty masks into ceramic sculptures that evoke hidden truths and the complexity of human emotions, reflecting humanity’s desire for an idealized self while exposing the risks of self-deception and moral decay. Ou Yanshan’s work serves as a symbol of bodily memory, carrying women’s desire and shame, while embodying their ongoing struggle between social norms and personal longing.

Some artists turn inward, exploring memory, time, and lived experience. In Jacopo Dal Bello’s work, the traces of aging are smoothed over, exposing humanity’s desire to reverse nature and control life, along with the risk of time and the meaning of life being quietly altered. Jakub Šimčík reimagines kitchen utensils as vessels of memory, migration, and trauma, showing how these forces are embedded in ordinary objects and shape individual experience. Turning inward to explore the folly and fragility of human desire, Yiy Zhang’s sculpture shows how longings and unfulfilled wishes shape experience and also reveals that awareness of good and evil is inseparable from flaws and capacity for reflection.

Finally, the performances by the two artists offer a return to a more primordial state, inviting audiences to momentarily set aside the “forbidden fruit” within and experience vulnerability, bodily perception, and emotional flow, while rediscovering the freedom of relinquishing the desire to judge, define, and control. Tracing a psychological journey from inward retreat to reengagement with oneself, others, and nature, Samantha Bohatsch guides the audience through her reading performance, where nature becomes an active space for reflection and transformation and personal moments are turned into shared experiences. In Elana Katz’s performance, the slow melting of ice under participants’ body heat probes the delicate boundaries between pain, relief, and numbness, reflecting on humanity’s limited control over nature and the environment.

(Text by Qin Yan)

Footnotes

-

In ancient Hebrew, the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil is rendered as עֵץ הַדַּעַת טוֹב וָרָע (etz ha-daʿat tov vara). Here, daʿat means “knowledge,” “awareness,” or “experience”; tov means “good,” and ra means “bad” or “evil.” ↩

Announcement