The Uncanny Beauty of Efficiency

Excerpt of: Art and standards. DIN standards and RAL colors in Carsten Becker's work series DIN

Works Discussed

In the general consciousness, standards are anchored as foundations of social, technical, and economic developments, as organizing principles for precise and reproducible objects. Standards represent efficiency codified in regulations; standards bring order to the world in the Enlightenment tradition. Art, on the other hand, is often regarded as their antipode: as genius-driven, chaotic work that creates unique pieces. In fact, both spheres are connected by a centuries-old interplay full of inspiration, collaboration, and negotiation struggles. This can also be observed in the work of Berlin artist Carsten Becker; in his serial work cycle DIN (2019–2022), industrial standardized components meet conceptual photography.

The Duden defines standards as regulations, rules, and guidelines for products, materials, and procedures. Behind this, however, lies the search for standardization, for regularity, accuracy, and repeatability—all themes that also played a role in the history of art, such as in the Conceptual and Minimal Art of the 1960s and 1970s. But the search for ideal proportions, for example in the form of the so-called Golden Section, the Vitruvian Man, and Middle Eastern ornaments, also testifies to a long and inspiring interaction between standardization and art. For instance, there was debate about the extent to which nature, with its ability to form patterns, repetition, and efficient form—for example in inflorescences and leaf veins—was proof of divine omnipotence. Serial work, too, which until the modern era was about proving artistic skill through the exact repetition of an existing form, anticipates industrial and military standards, whose early history concerned the interchangeability and accurate equality of screws and weapon parts. In the modern era, artistic seriality then transformed more into a design and image-constituting concept that sought to combat hierarchies with uniformity and pursued the dissolution of the artist's self, as seen in the work of Ellsworth Kelly, On Kawara, or Hanne Darboven.

The economically and state-oriented standardization carried out for several decades by institutions such as the German Institute for Standardization (DIN), the Association française de normalisation (AFNOR), or the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), however, rarely plays a role in the spheres of art and culture. This is surprising for two reasons: first, standards largely determine everyday life in the 21st century, such as the paper format DIN A4 or the urban legend about EU regulations on banana curvature. Second, the Material Turn provided art studies with an intensive interest in artistic materials beyond bronze and oil paints. However, in architecture and design theory, based on the increase in standardized building components and manufacturing processes, a cyclical interest in the ambivalence of aesthetic and social implications of standards can be observed. Philipp Oswalt notes: "Standards are not neutral or objective, but contain an implicit, quasi-hidden agenda to which the visible and explicit dimension of standards (such as the specification of dimensions or components) is subordinated." These subcutaneous political, military, and aesthetic implications of standards have been addressed in Carsten Becker's work since 2017.

Standards in Carsten Becker's Work

In DIN, Becker focuses on standardized components that were developed for military and economic purposes. In framed photo prints measuring 42x59, 59x84, and 84x119 centimeters, for example, the club handle standardized in 1924 can be seen, which was used as an operating element for machines, or the Steinie-shape from 1953, colloquially called a 'bomb' when used as a beer bottle. Becker's objects have in common that they were standardized to be mass-producible on different machines by different manufacturers. They all follow standards of DIN, founded in 1917. At that time, the idea of standardizing the world of objects was in the air, as evidenced by the German Product Book published in 1915 by the Dürerbund-Werkbund-Genossenschaft.

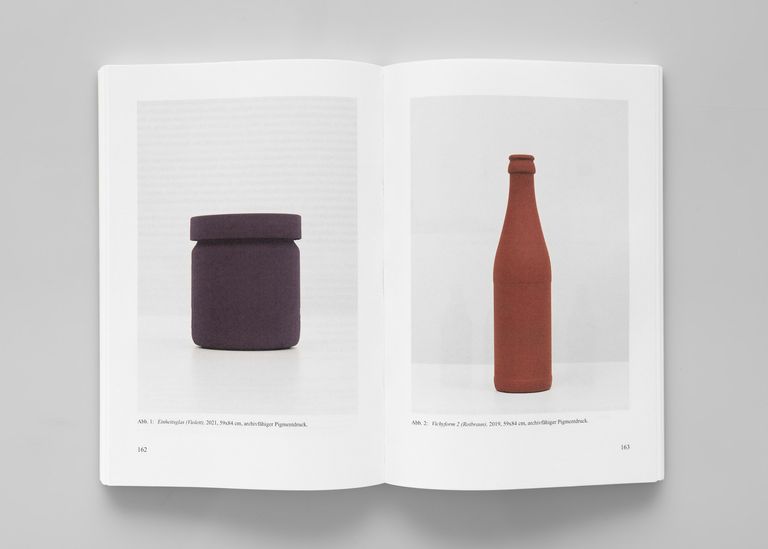

Through the complex technical process of macro photography, known for its razor-sharp image quality, Becker directs the viewer's gaze to the clear forms of the standardized components. The simplest explanation for their pleasing appearance is the perfection of their axially symmetrical contours, such as the elongated, convex curve of the club handle, and the proportional composition of the parts, as seen in the one-to-two-thirds ratio of the bottles in Euro-shape 2 (Olive Green, Chocolate Brown) (Fig. 4). These representatives of universal form appear in Becker's work as apologists for the beauty of industrial manufacturing, as if Adolf Loos' polemic Ornament and Crime (1908) and Hermann Muthesius' conception of the "standard of good form" had become reality. Through the medium of photography, Becker transfers these everyday objects into the infinity of a white space, familiar to viewers as the white cube of the art gallery. Removed from their functional context in this way, the curves, undulations, grooves, lines and edges of the objects cannot be overlooked. As industrial objets trouvés, as archetypes of everyday objects, Vichy-shape 2 (Red Brown) (Fig. 2), for example, shows the elegance of the ascending form, while Standard Glass (Violet) (Fig. 1) reveals a graceful interplay of curves and edges. Others, such as the curved captive C-washer and the smooth ball knob, radiate a sublime tranquility in their abstract unrecognizability.

The colors chosen by Becker contribute to this impression; only through them does he transform the infinitely repeatable into unique pieces, allowing them to diffuse through Becker's treatment into the sphere of art. Their matte colors absorb light, so that the razor-sharp contours make them appear flat. Within the interior form, however, the colors direct the viewer's gaze to the three-dimensional shadows and highlights of these everyday sculptures.

Becker painted these representatives of universal forms with tones from the German RAL color collection, which is named after the Reich Committee for Delivery Conditions, founded in 1925. It continues to catalog colors used by German authorities and the military to this day. Although designed for infinite repetition, some of these RAL colors proved finite: RAL 4000, the violet of the luxury train Rheingold that ran from 1928 to 1939 on Becker's standard glass, and Dark Yellow, the color used for camouflage against infrared night vision devices on his ball knob, were removed from the color register after World War II. Other colors have survived in the color collection but have undergone changes in formulation and color effect, such as Black Grey (also called Panzer Grey) or Ivory.

Historical Contexts as an Aspect of Conceptual Photography

Carsten Becker pursued these buried wartime standard colors: For the series RAL (2017–2021), he collaborated with Jürgen Kiroff from Fürth, who took over the archive of the German Institute for Quality Assurance (RAL) in 2009, the successor institution to the Reich Committee for Delivery Conditions. Using old RAL color cards, formulations, and archival documents, they reconstructed the tonality of colors that were no longer available or no longer available in their original tone. Since some of their components are no longer manufactured today, numerous experiments were required to achieve an authentic approximation of the historical color effect. Becker also pursued this approach in the subsequent series Agfacolor (2018–2021), which draws from color slides taken by German propaganda soldiers in the 1930s.

During Becker's research for the DIN series, it became clear that not only is the history of RAL color usage partly unexplored, but the history of numerous DIN standards is also difficult to reconstruct. Nevertheless, Becker identified numerous standardized components that were standardized during World War II or were used for weapons and military equipment, such as the ball knob standardized in 1937. This also includes the Vichy-shape, named after Vichy, the French spa town and seat of General Pétain's regime that collaborated with the National Socialists, as well as an outpost of AFNOR, regulated by Germany; the bottle shape was first standardized by DIN in 1942. In Becker's conceptual photography, these historical-military contexts seem to lie directly beneath the flawless color layer and in the shadows of the perfectly formed metal parts.

Becker, whose grandfathers participated in World War II, uses artistic means to reveal the entanglement of technical standardization, standardized warfare, and aesthetic efficiency. Indeed, some of the earliest examples of standardization can be found in the military context, such as when infantrymen of the Brandenburg-Prussian army were required by electoral decree from 1691 to wear exclusively blue uniform jackets. From this pre-industrial understanding of standardization as a conceptual offspring of normalization stems the connection between the normal and the ideal-typical, as echoed in Kant's "aesthetic normal idea" and Carl Gustav Carus' concept of 'fate.' The armaments industry was thus an innovation driver for standardization from the beginning: during the Coalition Wars, the French army benefited from the first standardized and thus interchangeable weapon components, which master gunsmith Honoré Blanc had mass-produced for muskets from 1785 onwards. Standardization aimed at arbitrary interchangeability meant masterful craftsmanship in this early industrial period and was therefore expensive, but paid off in the form of military superiority: Blanc introduced the practice of manufacturing handmade parts as consistently as possible using templates, gauges, and master models. Military and industry subsequently inspired each other: around 1800, the Englishman Henry Maudslay invented a lathe for standardized screw threads that any nut of the same size could fit. This event, or even Joseph Whitworth's 1841 lecture On an Uniform System of Screw Threads, is often cited as the birth of standardization, disregarding the early military implications of standardization. However, there can be no doubt about this connection: the Standards Committee of German Industry, predecessor of DIN, was founded on December 22, 1917, on the initiative of the Royal Manufacturing Office for Artillery. In March 1918, it published the symbolically significant DIN standard 1 "Taper Pins": versatile objects used both in mechanical engineering and in weapons such as the machine gun 08/15. Standards were also highly valued during World War II: in 1939, DIN standards became legally binding. However, DIN competed with Nazi institutions for its own impact on the efficiency increases crucial to the war effort, such as the Reich Committee for Performance Enhancement (RfL), founded in 1938/39 for armament purposes, and the Reich Committee for Delivery Conditions, which had originally only been active in the field of quality standards. As in 1917, DIN was also of great value to the military this time: military equipment such as the MG 34, grenades, and aircraft types were continuously standardized, and the administration of occupied territories and concentration camps could only reach its incomprehensible dimensions through DIN standardizations in data processing.

Military, Form, and Color

These military material and efficiency battles of World War II, which also left scars in his family, Carsten Becker seeks to comprehend in his work through their silent accomplices. In the perfection of his photographs and in the beauty of the standardized forms, Becker brings to light an oppressive foundation. His works expose the entanglements of modernist formal discourse with the horror of the Holocaust; they reveal the interconnections of aesthetic color theories with the dehumanizing regime of National Socialism. In Carsten Becker's work, forms and colors are not universal and apolitical, but components of visual, social, and political rhizomes that resurface in 21st-century everyday life, for example as 'Vichy-shape.' Despite all their attention to detail, Becker's photographs thus do not fulfill the belief in the truthfulness of photography as a technical medium. Instead, he stimulates perception of contextual connections: viewers are called upon to decipher for themselves the intra-pictorial network of white cube, technical form, and photographed color.

Published in

Kunst und Werk: Jahrbuch Technikphilosophie 2022, ed. Alexander Friedrich et al., Baden-Baden 2022, pp. 157–173, ISBN 978-3-8487-7300-8

Article as PDF from Nomos Verlag ↗ | Order complete issue ↗

Errata

The following corrections have been made to the original text:

- "Elsworth Kelly" corrected to "Ellsworth Kelly".

- "Philipp Oswald" corrected to "Philipp Oswalt".

- Subheadings omitted in the print edition have been restored from the original manuscript.